December 30, 2025

Databricks vs Snowflake: How to Choose the Right Platform for Enterprise AI

Author:

CEO & Co-Founder

Reading time:

24 minutes

Snowflake and Databricks are no longer just data platforms – they are competing visions for how enterprises will build and use AI. Both promise faster insights, safer data, and smarter systems, and both increasingly claim to do the same things. Yet beneath the overlapping feature sets lies a fundamental difference in philosophy: one is designed to make AI easy to apply, the other to make AI possible to engineer.

This article cuts through the marketing noise to explain how Snowflake and Databricks actually differ in architecture, governance, cost, and day-to-day workflows – and how those differences should shape platform decisions as AI moves from experimentation into production.

Key Takeaways:

- This is no longer a “warehouse vs lake” decisionSnowflake and Databricks are both evolving into full data-and-AI platforms. The real difference is how they approach AI, governance, and user experience.

- Snowflake prioritizes speed, safety, and business adoptionIt’s designed to help organizations apply AI quickly using existing data and skills, with strong guardrails and minimal operational effort.

- Databricks prioritizes flexibility, control, and engineering depthIt’s built for teams that want to design, train, and evolve AI systems as a core capability, not just consume AI features.

- Data for AI matters more than modelsAccess to models is increasingly commoditized. What determines success is how well your data is prepared, governed, and operationalized for AI.

- The gap between the platforms is shrinking, but the mindset difference remains

- Both Snowflake and Databricks are moving toward each other’s strengths, yet their core philosophies still shape how teams work day to day.

Snowflake and Databricks have become the two centers of the enterprise data and AI market. Any serious conversation about data analytics, machine learning, or Generative AI eventually circles back to these two platforms – and to the very different instincts they embody.

Watching their rivalry today feels a bit like revisiting an old enterprise software story: the tension between platforms designed to deliver fast, packaged value and those built to become deeply embedded systems of record. Think Salesforce and SAP – not as categories, but as mindsets.

Snowflake leans into polish, abstraction, and immediacy. It promises that working with data – and now AI – should be frictionless, safe, and accessible to business teams from day one. Databricks, on the other hand, grew up in the open-source world, where flexibility, control, and engineering depth matter more than guardrails. It assumes AI is not something you simply turn on, but something you build, evolve, and operationalize over time.

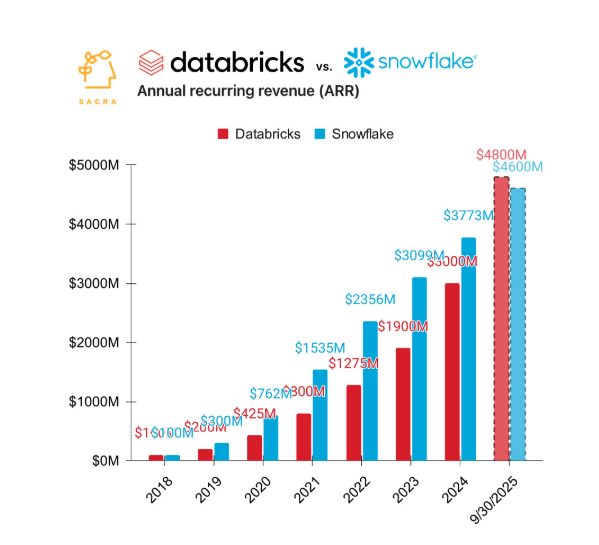

The market is clearly reacting to this contrast. Databricks’ rapid growth and elevated private valuation reflect growing confidence that AI platforms will increasingly resemble foundational enterprise systems rather than standalone tools. From a business perspective, this suggests belief in Databricks’ long-term role, but it also comes with risk. High valuations amplify expectations, and the challenge shifts from technical excellence to proving consistent, organization-wide business impact.

Snowflake, meanwhile, remains the public-market heavyweight with a massive enterprise footprint and a stronghold in analytics. Its task is to extend that success into AI without losing the simplicity that made it attractive in the first place, a balance every enterprise SaaS leader eventually has to strike.

Source: Sacra Newsletter

Beneath the sales-driven comparisons and competitive scorecards, both companies are responding to the same underlying shift. In the AI era, models themselves – whether large language models, predictive algorithms, or open-source alternatives – are no longer the scarcest resource.

What truly differentiates outcomes is Data for AI: the ability to prepare, govern, and operationalize trusted enterprise data so it can reliably power analytics, machine learning, and generative systems in production. Without it, AI initiatives collapse under hallucinations, opaque decisions, governance gaps, or uncontrolled costs.

This report explores Snowflake and Databricks through that lens. Rather than treating the choice as binary or declaring a clear winner, it examines how each platform’s architecture, governance approach, AI capabilities, and economics align with different organizational realities.

The real question is not which platform is “better,” but which mindset – and which trade-offs – fit an organization’s AI ambitions today.

The sections that follow provide a practical framework to help decision-makers navigate that choice, grounded in how these platforms operate in practice, not just how they market themselves.

Databricks vs Snowflake: Quick Comparison

| Feature Category | Snowflake | Databricks |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Managed Cloud Data Warehouse (SaaS) | Open Lakehouse (PaaS) |

| Primary Language | SQL (Python via Snowpark) | Python/Scala/SQL (Spark) |

| GenAI Model Access | Cortex: Serverless access to top LLMs. Easy, managed. | Mosaic AI: Model Serving for any model (Open/Custom). Flexible. |

| RAG Implementation | Cortex Search: Managed vector search service. Quick setup. | Vector Search: Fully integrated with Unity Catalog. Scalable, tunable. |

| Data Governance | Horizon: RBAC, object-level security. “Walled Garden.” | Unity Catalog: Lineage, file-level & model governance. “Open Umbrella.” |

| Cost Model | Credits: Predictable, auto-suspend. Premium pricing. | DBUs: Efficient for batch/scale. Spot instance savings. |

| Open Formats | Iceberg: Support via External Tables/Polaris. | Delta Lake: Native format. Iceberg supported via Uniform. |

| Low-Code Tooling | Streamlit: Python-to-UI for data apps. | Lakehouse Apps: Emerging framework for data apps. |

| Business User AI | Cortex Analyst: High accuracy text-to-SQL agent. | Genie: AI/BI assistant for complex data questions. |

Why Snowflake and Databricks Feel So Different

Snowflake and Databricks were built with very different assumptions about who data platforms are for and how they should scale.

Those early design choices still shape their architectures, product decisions, and AI strategies today, defining not only what each platform does well, but also the trade-offs organizations continue to navigate.

Snowflake: Built for Analysts and Business Teams

Snowflake was founded in 2012 by Benoît Dageville, Thierry Cruanes, and Marcin Żukowski. With Dageville and Cruanes coming from Oracle and its core insight emerged from frustration with rigid architectures that struggled to scale and, in particular, failed to handle concurrency.

As the founders put it:

“Our mission was to build an enterprise-ready data warehousing solution for the cloud,” a vision formalized in The Snowflake Elastic Data Warehouse paper.

That early focus on reliability, performance isolation, and ease of use continues to shape Snowflake’s platform decisions today – especially as it expands toward AI-driven workloads.

Snowflake’s foundational DNA can be summarized as follows:

- Enterprise-first, RDBMS-based design

Snowflake is grounded in relational database principles and optimized for structured analytics. By standardizing on SQL, it aligns directly with existing enterprise skills, enabling analysts and business teams to adopt advanced analytics and AI capabilities without retooling or retraining. - Product-led simplicity over platform complexity

The platform is intentionally designed to abstract complexity. Rather than exposing tuning parameters and architectural choices, Snowflake prioritizes predictable behavior and a consistent user experience, reducing friction for non-technical users and lowering the cost of adoption across the organization. - Fully managed SaaS operating model

Snowflake removes infrastructure management from the equation. There are no servers to provision, no indexes to tune, and no clusters to maintain. For IT leaders, this translates into lower operational overhead, fewer specialized roles, and clearer accountability for performance and availability. - Separation of storage and compute for workload isolation

By decoupling storage from compute, Snowflake allows organizations to scale analytics and AI workloads independently. Compute resources can be provisioned on demand via isolated virtual warehouses, ensuring that experimentation, reporting, and AI inference do not interfere with each other. - Proprietary, tightly controlled execution layer

Snowflake deliberately maintains a closed architecture, controlling storage formats, query optimization, and execution. This limits customization but delivers predictable performance, strong governance, and operational stability – traits that become increasingly important as AI workloads move into regulated and business-critical environments.

Databricks: Built by Engineers, for Engineers

Databricks was founded in 2013 – just a year after Snowflake – but emerged from a very different intellectual background. Its founders, including Ali Ghodsi, Matei Zaharia, and Ion Stoica, came from UC Berkeley’s AMPLab and were the original creators of Apache Spark, the open-source engine that redefined large-scale data processing.

As a result, Databricks’ DNA is deeply rooted in distributed computing and open-source software.

While Snowflake was built around structured data and SQL-based analytics, Databricks set out to address the classic “three Vs” of big data: volume, velocity, and variety. It was designed for data engineers and data scientists who needed to process massive amounts of unstructured and semi-structured data – such as logs, images, and sensor streams, using programmatic languages like Python, Scala, Java, and R.

From the beginning, Databricks positioned itself as an open platform rather than a walled garden. It embraced the data lake as the central repository for enterprise data, allowing organizations to store information in its raw form.

Early data lakes, however, often devolved into “data swamps,” lacking governance, reliability, and transactional guarantees. Databricks addressed this gap by introducing the Lakehouse architecture, adding a transactional layer through Delta Lake to combine the flexibility of a data lake with the reliability and consistency of a data warehouse.

The platform’s early users were highly technical by design. Databricks targeted engineers and data scientists who wanted full visibility into execution, the ability to tune clusters, and the freedom to build complex machine learning pipelines from the ground up.

As a result, Databricks earned a reputation as a builder’s platform – exceptionally powerful and flexible, but demanding a higher level of technical expertise to operate effectively.

Where Snowflake and Databricks Are Starting to Overlap

As of late 2024 and heading into 2025, the strategic distinction has blurred significantly. Snowflake is aggressively courting data scientists with Snowpark (allowing Python execution) and marketing its AI Data Cloud.

Databricks is pursuing business analysts with Databricks SQL (a serverless warehouse experience) and Genie (AI-powered BI).

Despite this convergence, the DNA persists:

- Snowflake approaches AI as a service to be consumed – focusing on safety, governance, and ease of integration for existing business data.

- Databricks approaches AI as a system to be engineered – focusing on model training, fine-tuning, and the orchestration of complex “compound AI systems”.

How Snowflake and Databricks Are Architected

For a business leader, the underlying architecture matters because it dictates cost, speed, and the feasibility of future AI projects.

The central debate in 2025 was between the “Managed Warehouse” model and the “Open Lakehouse” model.

Snowflake’s Architecture: Managed and Predictable

Snowflake’s architecture is characterized by a central data repository that is fully managed by Snowflake.

When data is loaded into Snowflake, it is converted into a proprietary, optimized file format. This conversion enables Snowflake’s query performance and concurrency scaling but historically created a form of “data lock-in,” as the data could only be accessed via the Snowflake engine.

Key architectural features:

- Multi-cluster shared data architecture: Separate compute clusters can access the same shared data simultaneously without contention. This is critical for serving AI models and BI dashboards concurrently. The central services layer handles metadata, transaction management, and security, ensuring that all users see a consistent view of the data.

- Serverless maintenance: Automatic clustering, vacuuming, and optimization are handled by the platform, reducing the need for database administrators (DBAs). This automation is a significant driver of TCO reduction, as it frees up engineering talent from mundane maintenance tasks.

- Snowpark container services: To support AI, Snowflake has introduced container services that allow developers to run arbitrary code (including custom AI models) directly inside the Snowflake security perimeter. This minimizes data movement, a crucial factor for security and latency.

The Snowflake architecture offers the highest level of “peace of mind.” The platform guarantees data consistency and security, making it ideal for highly regulated industries like finance and healthcare where data governance is paramount. The trade-off has historically been cost and flexibility, although recent moves toward open formats are mitigating the flexibility concern.

Databricks’ Architecture: Open and Flexible

Databricks advocates for a “Lakehouse” architecture. In this model, data resides in open formats (primarily Parquet/Delta Lake) in the customer’s own cloud storage account (AWS S3, Azure Blob, Google Cloud Storage).

Databricks provides the compute engine to process this data, but the data itself is decoupled from the engine.

Key architectural features:

- Decoupled storage and compute ownership: Customers retain full ownership and physical control of their data files. If they choose to stop using Databricks, the data remains in their storage buckets in an open format, accessible by other engines. This architectural choice provides significant leverage in vendor negotiations and future-proofing strategies.

- Unified engine: The same Spark-based engine is used for data engineering (ETL), data science, and SQL analytics. This reduces the friction of moving data between different systems for different teams. The introduction of Serverless SQL warehouses has further simplified the compute model, allowing Databricks to offer instant elasticity similar to Snowflake.

- Photon engine: To address the performance gap with traditional data warehouses, Databricks developed Photon, a vectorized query engine rewritten in C++. This engine brings data warehouse-level performance to the data lake, allowing Databricks to compete directly with Snowflake on structured data workloads.13

The Databricks architecture offers “future-proofing.” By keeping data in open formats, organizations avoid vendor lock-in and can easily experiment with new AI tools that may emerge in the open-source ecosystem. It is particularly well-suited for organizations with massive volumes of unstructured data that would be prohibitively expensive to load into a proprietary warehouse.

Iceberg vs Delta Lake: Why Open Formats Matter

A critical subplot in this architectural war is the rise of Apache Iceberg.

Iceberg is an open table format that brings warehouse reliability to data lakes, similar to Databricks’ Delta Lake.

- Databricks championed Delta Lake, which is open-sourced, but it remains heavily associated with the Databricks ecosystem. Databricks has recently expanded its Unity Catalog to support Iceberg via the Iceberg REST Catalog API, enabling interoperability.

- Snowflake, recognizing the market demand for open storage, has pivoted to embrace Apache Iceberg aggressively. Snowflake’s Polaris Catalog is an open-source catalog for Iceberg, reinforcing the industry’s shift toward interoperability.

This is a defensive move for Snowflake and an offensive one for Databricks. Snowflake’s support for Iceberg means customers can now manage data in their own storage (like the Databricks model) while using Snowflake as the query engine.

For a business kicking off an AI initiative, this means data stored in an open lake can now be accessed by Snowflake’s Cortex AI tools without expensive ingestion processes.

How Snowflake and Databricks Approach Generative AI

The primary driver for recent platform investments is Generative AI. As businesses move from “data collection” to “intelligence generation,” the platform that best supports AI workflows will win the enterprise.

Both vendors have launched comprehensive suites to capture this market: Snowflake Cortex and Databricks Mosaic AI.

Snowflake Cortex: The “Apple-like” Approach to AI

Snowflake’s AI strategy focuses on democratization and safety. Cortex is a fully managed service that provides access to industry-leading Large Language Models (LLMs) (like Meta’s Llama, Mistral, and Snowflake’s own Arctic) via simple SQL functions.

What this means in practice:

- No infrastructure to manage

AI runs as a service. There are no GPUs to provision, no environments to tune, and no pipelines to maintain. Users simply call AI functions from SQL, which dramatically lowers the barrier to adoption and speeds up time to value. - AI-powered search over enterprise data

Cortex includes a built-in search capability that makes internal documents searchable by AI. This enables common use cases like “chat with your policies” or “ask questions about internal documents” without complex setup or tuning. - Conversational analytics for business users

Instead of navigating dashboards, business users can ask natural-language questions about their data (e.g., “Why did sales decline last quarter?”). Snowflake translates these questions into governed queries, ensuring answers are consistent with business definitions. - Structured data from unstructured documents

Snowflake also provides built-in document processing, turning PDFs and invoices into structured, queryable data. This is especially useful for automating workflows and feeding AI applications with reliable inputs.

Cortex is ideal for organizations that want to apply Gen AI to their data immediately with minimal engineering overhead. It is a “low-code” solution. The trade-off is flexibility; you are generally limited to the models and fine-tuning options Snowflake provides, although this is changing with the ability to bring custom models via Snowpark Container Services.

Databricks Mosaic AI: The “Android-like” Approach to AI

Databricks approaches AI from the opposite direction. Instead of prioritizing ease of use, its Mosaic AI platform is designed for organizations that want to build AI systems as a core capability, not just apply AI to existing workflows.

The emphasis is on flexibility, control, and scalability. Databricks assumes AI will be deeply embedded into products and processes – and that engineering teams need the tools to customize every layer.

What this means in practice:

- Custom model training and fine-tuning

Databricks supports training models from scratch or fine-tuning open-source models on proprietary data. This is critical for organizations that need highly specialized models – such as in healthcare, finance, or manufacturing – where generic models are not sufficient. The platform manages GPU orchestration and scaling, but model design remains in the hands of the team. - AI agents and multi-step workflows

Mosaic AI includes tools for building advanced, agent-based systems that can reason, retrieve data, and take actions across multiple steps. This goes well beyond simple “chat with your data” use cases and enables automation of complex business or operational workflows. - Scalable search and RAG for large systems

Databricks offers a vector search tightly integrated with its data and ML tooling. It is built for scale, supports hybrid search (semantic + keyword), and connects directly to model experimentation and evaluation workflows. Compared to Snowflake’s more turnkey approach, this requires more setup but offers greater control. - AI-powered analytics with transparency

Genie is Databricks’ conversational analytics interface. It allows users to ask business questions in natural language, similar to Snowflake’s Cortex Analyst. The difference is emphasis: Genie exposes the generated logic and supports complex scenario analysis, which appeals to advanced users but can feel less immediate for purely non-technical teams.

Mosaic AI is the choice for “AI-native” companies or enterprises with mature data science teams. If the goal is to build a competitive advantage through a unique, proprietary model, Databricks provides the necessary tooling. It offers a “glass box” approach where engineers can see and modify every part of the system.

Example: Building a RAG Chatbot in Snowflake vs Databricks

To illustrate the practical difference between the two approaches, consider a common use case: a RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) Chatbot that answers employee questions based on internal PDF handbooks.

Scenario: An HR department wants a chatbot to answer questions about benefits from 5,000 PDF documents.

Snowflake workflow:

- Fast setup, minimal engineering

PDFs are uploaded, text is extracted, search indexing is created, and AI responses are generated largely through built-in services. - Low operational effort

Snowflake automatically handles document parsing, embeddings, search, and scaling in the background. - Business-friendly development

The solution can be built using SQL and light Python, with a simple internal app created directly within Snowflake.

Result: A working chatbot can be delivered in days – or even hours – by a small team, with security and governance handled by default.

Databricks workflow:

- More setup, more control

Data ingestion, indexing, and model configuration are explicitly defined, giving teams full control over how the system behaves. - Built for measurement and improvement

Before launch, teams can test accuracy, relevance, and hallucination risk using built-in evaluation workflows. - Flexible deployment options

The chatbot can be integrated into broader applications or platforms and optimized over time.

Result: A more robust, tunable system designed for long-term use, higher accuracy, and evolving requirements.

Snowflake wins on speed to MVP (Minimum Viable Product) and ease of use for lean teams. Databricks wins on optimization, evaluation, and scale for mission-critical applications where every percentage point of accuracy matters.

Security and Governance: Snowflake vs Databricks

An AI model that inadvertently leaks sensitive customer data is a catastrophic risk. The governance models of Snowflake and Databricks reflect their architectural histories.

Databricks Unity Catalog: One Governance Layer for Data and AI

Databricks’ Unity Catalog is a unified governance layer that sits across data, AI models, and analytics. Its superpower is its breadth. It governs files, tables, ML models, and dashboards in a single interface.

- Openness: Databricks recently announced that Unity Catalog is being open-sourced. This suggests a future where Unity Catalog could govern data even outside of the Databricks platform, reinforcing their “open ecosystem” strategy. This allows for a unified view of data across AWS, Azure, and GCP, which is critical for multi-cloud strategies.

- Data Lineage: Unity Catalog provides automated lineage, showing exactly which column in which table fed into which AI model. This is critical for debugging AI hallucinations and regulatory auditing.

- AI Governance: It specifically addresses AI risks by governing Models (via Model Registry) and Features (via Feature Store) alongside data. It allows for rigorous access control over who can query a model endpoint.

Snowflake Horizon: Governance Built into the Platform

Snowflake Horizon is the brand name for Snowflake’s built-in governance suite. Because Snowflake controls the storage and compute tightly, its governance is incredibly granular and easier to enforce.

- Simplicity: Horizon features like “Dynamic Data Masking” and “Row Access Policies” are applied at the database object level. Once set, they apply universally, whether the data is accessed via SQL, Python, or an AI model. This creates a “secure by default” environment.

- Compliance: Snowflake has a long history of meeting high compliance standards (FedRAMP, HIPAA, PCI) with less configuration required than Databricks. It offers “out-of-the-box” security controls that are often manual in Databricks.

- Polaris: In response to Unity Catalog, Snowflake launched Polaris, an open-source catalog for Iceberg tables. This is an attempt to neutralize Databricks’ openness advantage, allowing Snowflake to govern data stored in external lakes.

For organizations with a messy, multi-cloud environment involving various tools, Unity Catalog offers a better “umbrella” to unify governance. For organizations that can consolidate their data gravity into Snowflake, Horizon offers a tighter, more seamless “fortress” that requires less administrative overhead.

Financial Analysis: Cost Models and TCO

The pricing models of Snowflake and Databricks are notoriously difficult to compare directly, often leading to “bill shock” if not managed carefully. Understanding the nuances of their economic models is crucial for forecasting the ROI of AI initiatives.

Snowflake: The Utility Model (Credits)

Snowflake charges based on Credits. You pay for the time a Virtual Warehouse is running.

- Pros: Highly predictable. You can set strict limits (e.g., “Suspend after 5 minutes of inactivity”). The pricing includes the management overhead (SaaS premium).

- Cons: Can be expensive for “always-on” workloads. The mark-up on the underlying cloud compute is significant because you are paying for the managed service.

- AI costs: Cortex functions are metered by tokens (input/output volume), similar to OpenAI’s API pricing. This is a pay-as-you-go model that scales linearly with usage. This is advantageous for sporadic usage but can become costly at very high volumes.

Databricks: The Efficiency Model (DBUs)

Databricks charges based on Databricks Units (DBUs). This is a measure of processing power.

- Pros: Generally lower cost per unit of compute for massive batch processing jobs (ETL). Spot instance support allows for significant savings on non-critical workloads.

- Cons: Historically harder to predict. A poorly written Spark job could run inefficiently and burn DBUs. However, Serverless SQL warehouses are normalizing this to look more like Snowflake’s model.

- AI costs: For Mosaic AI, you pay for the compute to host the model (Model Serving). This is often an “always-on” cost if you need real-time inference, which can be more expensive than per-token pricing for low-volume use cases but cheaper for high-volume, predictable workloads.

Hidden Costs of AI

- Data egress: Moving data out of a platform to train a model elsewhere incurs egress fees. Snowflake’s “Data Cloud” creates gravity; keeping data and AI models inside minimizes this cost.

- Fine-tuning: Fine-tuning an LLM on Databricks requires spinning up GPU clusters. This is a capital-intensive activity. Snowflake’s managed fine-tuning (Cortex) abstracts this but likely includes a service premium.

- Operational overhead: Databricks often requires more engineering hours to manage and optimize clusters (though serverless is reducing this). Snowflake saves on engineering hours but charges a premium on compute. The TCO calculation must balance cloud spend vs. people spend.

Databricks often wins on price-performance for heavy data processing and large-scale model training. Snowflake often wins on administrative TCO, saving money on engineering hours required to manage the system.

Which Platform Should You Choose?

The decision between Snowflake and Databricks is no longer about “Warehouse vs. Lake.” It is a strategic choice about your organization’s AI philosophy and operational DNA.

The “Buy & Apply” Strategy (Snowflake)

Choose Snowflake if:

- Speed to Value is paramount: You want to enable business units to use GenAI on their data now with minimal setup. The ability to just “turn on” Cortex and have a working RAG pipeline is a game-changer for speed.

- Governance is non-negotiable: You operate in a highly regulated industry and prefer a “walled garden” approach to security where compliance is baked into the platform.

- Talent constraint: Your team is SQL-heavy, and you lack deep Python/Spark engineering resources. You want to empower your existing analysts to do more.

- Use Case: Your primary focus is Analytics, BI, and “Chat with your Data” applications (RAG) that serve internal business users.

Primary Risk: Higher operational costs for compute (the “convenience tax”) and potential limitations in customizing AI models if your needs become highly specialized.

The “Build & Differentiate” Strategy (Databricks)

Choose Databricks if:

- AI is your product: You are building AI features that require custom models, fine-tuning, and deep control over the training loop. You need the “factory” tools to iterate on models.

- Scale is massive: You process petabytes of unstructured data and need the cost efficiencies of the open lakehouse. The economics of processing huge datasets are generally better on Databricks.

- Engineering culture: Your team consists of software engineers and data scientists who prefer code over SQL. They want access to the underlying APIs and infrastructure.

- Use Case: Your primary focus is complex Machine Learning, Predictive Analytics, and automated Agentic workflows that go beyond simple text generation.

Primary Risk: Higher complexity in setup and management (though decreasing with Serverless) and a steeper learning curve for business users.

Increasingly, large enterprises are adopting a hybrid strategy. They use Databricks for heavy data engineering and model training (the “Factory”) and Snowflake for serving data to business users and analysts (the “Showroom”).

With the advent of open formats like Iceberg and Delta Lake, this hybrid model is becoming easier to maintain. Data can reside in an open lake (managed by Databricks or independent storage) and be queried by Snowflake for high-concurrency BI, while Databricks handles the heavy ML training on the same data.

| Dimension | Snowflake | Databricks |

|---|---|---|

| Primary ecosystem focus | Business analytics & data applications | Data engineering, ML & AI systems |

| BI tool integration (Tableau, Power BI, Salesforce) | Very strong and mature out of the box | Good, but often requires more configuration |

| Dashboard performance | Excellent for concurrent, interactive BI | Strong, but usually needs tuning |

| Analyst experience | Simple, fast, SQL-first | Improving, more technical |

| Engineer experience | Limited customization | Deep control and flexibility |

| Data format | Historically proprietary; now supports Iceberg | Open by design (Delta / Parquet) |

| Vendor lock-in | Reduced with Iceberg, still opinionated | Low for data, moderate for platform logic |

| Portability | Data increasingly portable | Data portable; governance less so |

| Governance approach | Built-in, managed, opinionated | Deep, explicit, configurable (Unity Catalog) |

| AI governance | Simplified, low-code | Granular, end-to-end |

| Marketplace model | Native applications running inside Snowflake | Sharing datasets, models, notebooks |

| Security model | Apps run within customer account | Assets shared across environments |

| Multi-cloud strategy | Strong, but Snowflake-managed | Strong, customer-controlled |

| Typical time to value | Fast | Slower, but more scalable |

| Best suited for | Business-led analytics & fast AI adoption | Platform-led, mission-critical AI |

Conclusion: Snowflake and Databricks Are Moving Toward Each Other

Both Snowflake and Databricks are acutely aware of their historical trade-offs – and both are now actively working to neutralize them. The push toward low-code and no-code experiences is not incidental; it reflects a broader realization that winning the AI platform war requires reaching beyond core technical users.

- Snowflake has expanded downward into application and AI interaction layers. Streamlit enables Python developers to quickly build internal apps for business users, while Cortex Analyst allows non-technical users to query data using natural language. Together, these tools lower the barrier between governed data and everyday decision-making.

- Databricks has moved in the opposite direction, pushing upward toward accessibility. Genie introduces conversational access to data and AI outputs, while Lakeflow simplifies data ingestion and transformation through low-code ETL. These additions are designed to reduce reliance on specialized Spark expertise and make the platform more approachable for analysts and less technical teams.

What’s notable is not just the feature set, but the intent. Each platform is deliberately encroaching on the other’s traditional strengths – Snowflake reaching toward application-level AI experiences, Databricks toward business-friendly usability.

This mutual expansion is a clear signal that the competitive boundary between the two is eroding.

FAQ

Is vendor lock-in still a concern?

Less than it used to be. Open formats like Iceberg and Delta Lake make data more portable. The bigger lock-in today is not data – it’s governance, workflows, and organizational habits.

Can I use both Snowflake and Databricks together?

Yes, and many large enterprises do. A common pattern is using Databricks for heavy data engineering and model training, and Snowflake for analytics, BI, and business-facing AI use cases.

Is Databricks only for very technical companies?

No, but it is most effective in tech-forward organizations. Databricks is adding more low-code and business-friendly features, but its core strength is still flexibility and control.

Do I need data scientists to use Databricks?

In most cases, yes. Databricks shines when you have – or plan to build – strong data engineering and data science capabilities. Without them, the platform can feel overwhelming.

Do I need strong data engineers to use Snowflake?

Not necessarily. Snowflake is designed to work well with SQL-heavy teams and analysts. Advanced engineering helps, but it’s not required to get value quickly.

Is Snowflake or Databricks “better” for AI?

Neither is universally better. Snowflake is better if you want AI to be easy, safe, and immediately usable by business teams. Databricks is better if AI is something you want to build, customize, and treat as a long-term engineering asset.

Category: